Introduction

Since the mass popularization of the radio in the 1920s, music has become a major staple in American popular culture. From dance halls to road trip anthems to online streaming, music has always had an intimate way of connecting distant strangers and family members alike. Shared soundscapes have been so crucial in reflecting our values that entire decades and places have been characterized by specific artists and genres. As relevant today as it was fifty years ago, music taste of a time period truly captures the voice of the people.

For this reason, we believe popular music is an indespensible tool to gauge the United States’ general sentiments and interests. Though not a perfect measure of public opinion, the Top 100 Billboard songs do reflect the most widely played and commercially successful songs of the industry and thus, what the American public prefers at that particular moment. We are most interested in seeing how these songs show the relationship between sexism and pop culture, more specifically in how popular music has reflected attitudes on gender in the United States. In this project, we have chosen to focus on gender representation and its effects in the Top 100 Artists and Songs from the last five decades. We hope to answer the following:

Does a more representative gender ratio of the Top 100 artists per decade (1960-2010) change the gendered dialogue in the most popular song titles?

Our findings are based on the dataset “Evolution of Popular Music: USA 1960-2010” by the Royal Academy of Engineering Research Fellow, Matthias Mauch. This list compiled the Billboard Top 100 per every quarter for the entire fifty year period. To learn about how we processed this data and who our team is, visit About the Project.

Results/Discussion

We were curious at how the last fifty years of top songs reflected the gender discourse of this period and whether changes correlated with certain milestones in gender relations. We focused on whether increased female representation in the industry has changed gender discourse in song titles. Coming up with an array of visualizations and findings, we hoped to compare them with current gender and music history research to see where our findings fell in today’s academic conversation.

Given the effectiveness of music as a tool for societal analysis, it does not come to a surprise that a feminist lens has been taken to music studies before. Right away, we found our inferences on the connection between music and social views had merit. Within “The Representations of Femininity in Popular Music,” Professor Dibben discusses how the concept of femininity is not fixed, but rather created through cultural interpretations of popular music. Music, particularly top-rated songs that get continuously replayed, influence the beliefs of a variety of people from different social groups (Dibben 2009). Therefore, it is within reason that song titles and lyrics that portray women in a certain light, whether positively or negatively, become absorbed within everyday attitudes. This also means society’s idea on gender is malleable and that it is possible for mainstream artists to alter how women are portrayed.

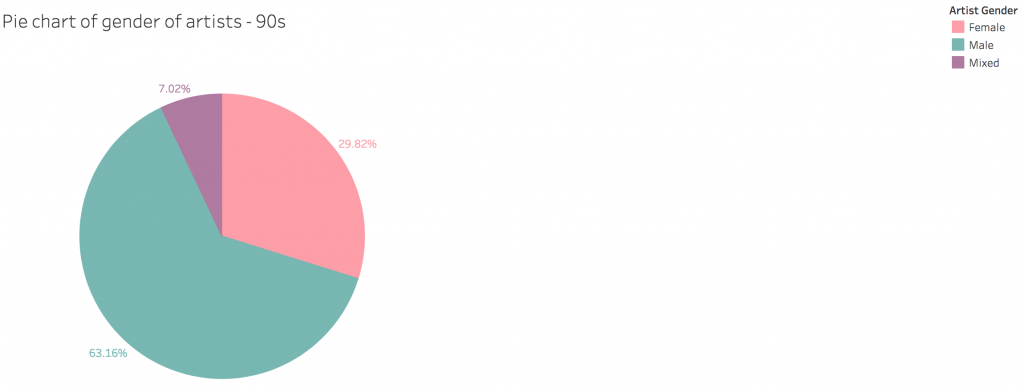

Pie charts of Top 100 artists gender

Above is a gallery of pie charts depicting the fraction of artists that are male, female and in mixed groups. The artists pooled are from the top 100 most popular artists from 1960 to 2010. We created this list by collecting the top 100 artists whose songs were mentioned the most amount of times in the entire data set. The mixed category corresponds to groups that include both female and male artists. We clearly see that for all fifty years, the share of male artists has been greatest and that the ratio of female artists has tripled over this time period.

Joseph Abramo’s “Popular Music and Gender in the Classroom” discusses the clear disparity between male and female artists in the music industry as seen above. Abramo studies the connection between popular music and gender identity. He discusses the importance of broadening the conversation of popular music in order to change how gendered discourse influences music production. Abramo argues that current discourses about male and female stereotypes create gender exclusion within popular music (Abramo 2009). As seen above, this is proven by our dataset “Evolution of Popular Music: USA 1960–2010,” by the underrepresentation of female artists within popular music. As Abramo discusses, there is a clear and crucial shift in the artists’ gender distribution over the past four decades towards more diverse representation.

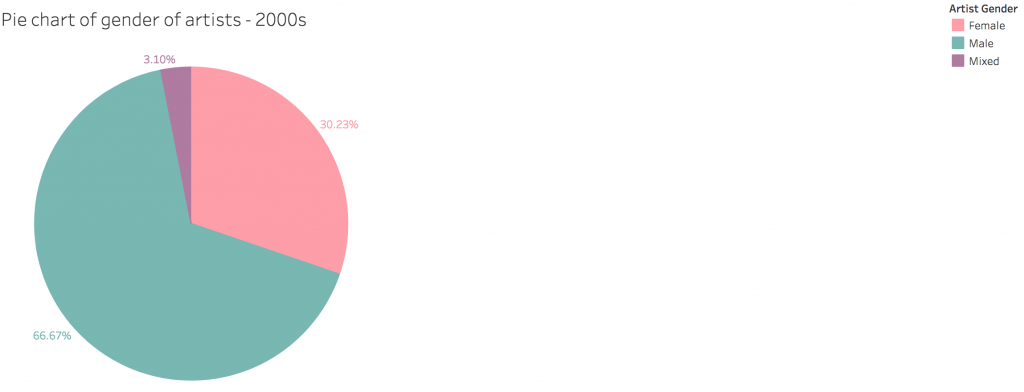

Treemap of artist gender

This treemap shows the popularity of specific top 100 artists and is sorted by their gender. The more an artist was mentioned in the top 100 song chart, the bigger their box. The size of the boxes is sorted from top to bottom and from left to right.

In “Claiming Space: Discourses on Gender, Popular Music, and Social Change,” Bjorck analyzes the challenges and attempts of women to create gender equality within popular music, an industry controlled by men. Bjorck acknowledges that gender of artists has a significant effect on the demography and hegemonies within popular music. Men have long dominated popular music genres including rock, rap, jazz, and pop (Bjorck 148). These correlations are clearly seen in our treemap as a more diverse genre of artists are displayed in the male category as compared to the female category. Understanding the nuances of genre and what spaces are available to women in the industry gives context to why the female artists have a similar “sound” in comparison to the male artists.

Bjorck describes how under-representation of the female gender in popular music is not just displayed by genders of artists in top charts, but also a matter of this space being claimed by men. Men have historically had control of media in the past and thus had a head start in gaining an audience base and continued support for their representation within music. Women, on the other hand, are pioneers to popular music, just beginning to solidify themselves in this space (Bjorck 148). In this case, women are not aiming to take over the space of men but rather create newer spaces in a constantly growing industry. These new spaces encourage positive depictions of femininity in different roles, open up more space for rising female artists, and promote gender equality.

Map of the birthplace of artists

This map shows us where the top 100 artists of our dataset (artists whose songs were mentioned the biggest amount of times in the entire data set) were born. Note that several popular artists in the United States come from outside the country, mainly the

Though relatively simple, we appreciate this visualization because it shows how music is truly a global experience and that artists bring their diverse backgrounds to their work. We theorize that relatively more diverse spread of successful female artists to the fact that limited resources in the music industry (Schmutz 2010) have lead women to succeed by looking for them in less traditional spaces. Despite the clear success several women have had in the East Coast among the plethora of male artists, the bundle of female artists in the LA area is significant.

Circle visualization of artist gender

This visualization is also about the popularity of the top 100 artists. It allows us to compare the popularity of artists by their number of records. We see that the most top records produced are from men and that only 1 woman from this dataset has produced more than 50 bestselling records.

This visualization appears deceiving, especially given all the incredible female artists we can instantly name off the top of our heads. However, the highest ranking album recorded by a female artist in the 2003 Rolling Stone’s Greatest Albums of all time was 30th. The truth is women have long received the leftovers when it came to music industry resources, including radio airplay and salary earnings. However, like other careers, this was not always the case as women were at one point equal to men in amount music production. Some experts liken this phenomenon to the gender exclusion in other careers such as the edging out of women by male writers and pianists in Victorian literature and Viennese musical respectively (Schmutz 2010). Regardless of success, our society’s sexism means stigma can easily be shifted to the benefit of male artists, leaving women to the outskirts. Given this disadvantage, women often have to rebuild network systems and fanbases creating the disparity that our visualization shows.

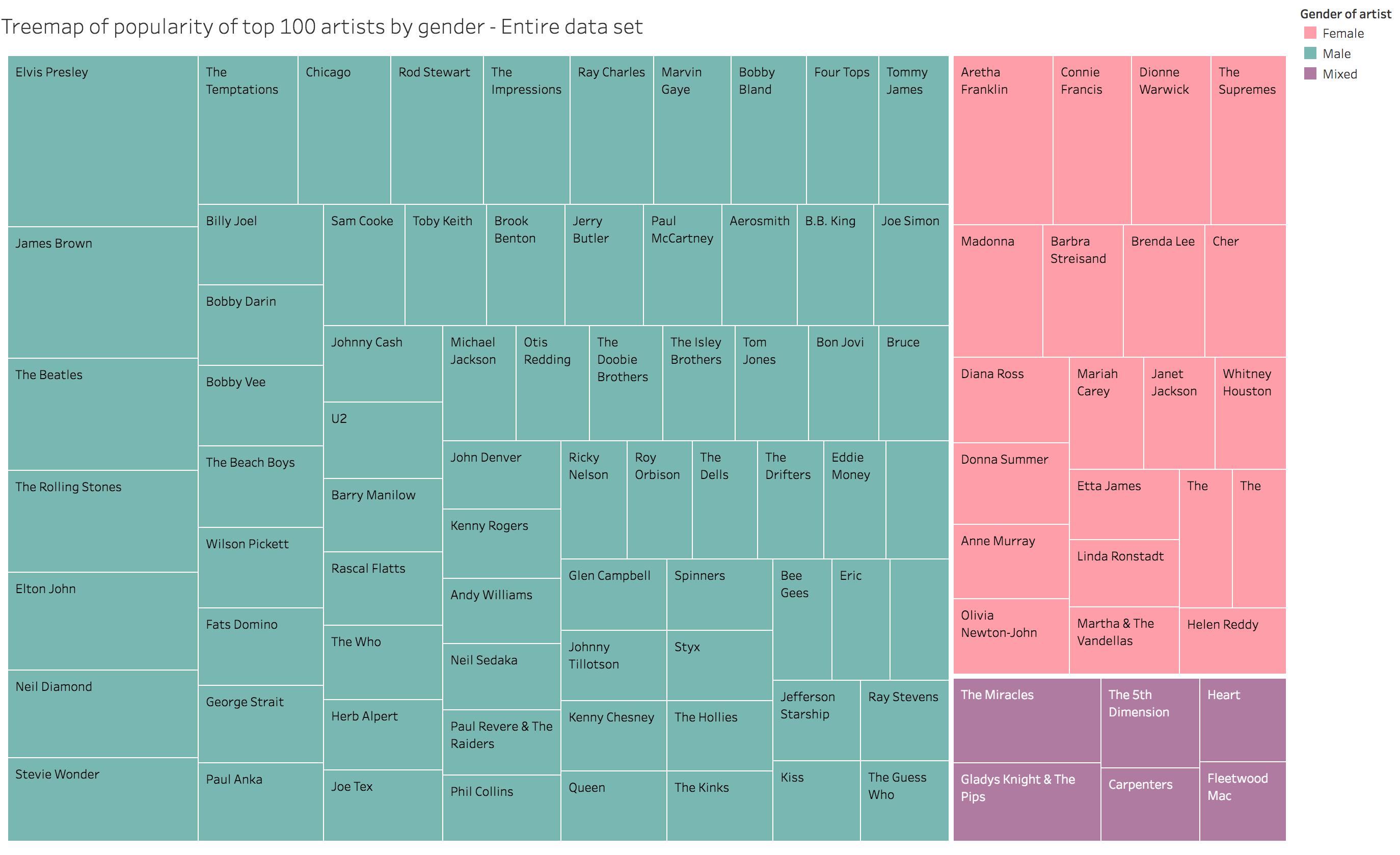

Gendered words compared to artist gender by decade

This visualization combines the share of male, female and mixed artists and groups for each decade and the count of gendered words (girl, woman, boy, and man) in each decade from the 1960s to the 2000s.

The artists are the top 100 most popular artists from each decade. We see that for most decades (except the 70s) “girl” is mentioned in song titles more than “woman”. On the contrary, in every decade “man” is more often mentioned than “boy”. This shows a difference in the way power and gender is portrayed. At the same time, we also see that the share of female artists rises over the decades along with an increase in the word “girl”. We believe these two events are not only a coincidence but in a causal relationship.

In “Acting Like a ‘lady’: Third Wave Feminism, Popular Music, and the White Middle Class,” Elizabeth Kathleen Keenan addresses the impact of popular music on feminism and vice versa. Keenan dives into the issue of the use of popular music as cultural politics within consumer culture. She claims that in the 1990s, there was a general consensus that there was a high amount of sexism within music in mainstream culture. Third Wave feminism then came into existence in the 1990s, attempting to renew activism through popular music that reached a young and fresh audience. (Keenan 2008) Towards 1999 and 2000, the amount of sexism within music started to change for the better. This occurrence supports our observation that the increased use in the word “girl” within popular songs may have represented a shift from a derogatory meaning to a meaning of empowerment during this time.

Network graph of words associated with “baby”

This is a network graph created with Palladio showing words commonly used in association with “baby”. As you can see, “your”, “my” and “me” show that baby is often used in terms of possession or command.

Interestingly, the word most commonly associated with “baby” in songs was “my baby” which is gender neutral but possessive. Commonly men refer to their partners as “baby” indicating male possession over the female. There is also the common use of “baby me”, which as a command indicates another power dynamic in relationships. Of course, we should note that both men and women are capable of using “my baby,” to reflect love and admiration for their partner.

In “Objectification in Popular Music Lyrics: An Examination of Gender and Genre Differences.” researchers set out to explore verbal objectification in multiple music genres including Rap, R&B/ Hip-Hop, Country, and Rock. They looked at the Top 20 Billboard songs from 2009-2013 and examined for keywords that fell into the realm of body objectification, male gaze, and attractiveness. Flynn and many of the other researchers’ findings came about similar conclusions to previous research: certain genres such as Rap and Hip Hop tended to use more objectification terms than other genres and that women tended to objectify themselves more than men did. Methods used for this study was a content analysis of lyrics used in popular songs. The findings concluded that 80% of R&B/Hip-Hop songs used some form of objectification or another (Flynn 2016). These trends agree with our research in that there are multiple gender biases towards men and women throughout music lyrics. However, they do also bring about a very important point for us to consider. This objectification and sexism are also perpetuated by women. Increased representation alone will not solely change attitudes in sexism. Instead, entire systemic attitudes must shift.

US Word Map

This is a word cloud of the words of the song titles of our entire data set. This is shaped like a map of the United States to give viewers an idea that these are the words associated with our national soundscape. The bigger the words the more they appeared in the song titles. This lets us know that the 5 most mentioned words are “love”, “baby”, “time” , “I’m” and “like”.

Men often portray women in media in demeaning and submissive ways within their lyrics, but popular women performers in the past have also been susceptible to following this trend. Historically, there have often been patriarchal constructions of femininity, making women appear to be a possession of men or at least easily controlled by them (Bjorck 148). While obviously these words are used by male and female artists, it does show that the U.S. responds well to song titles that reflect men in places of power. This visualization shows that “man” has been used more over the last few decades instead of “boy,” whereas “girl” has been used more to represent the female gender, as opposed to “woman.” This hints a more mature view of the male gender within popular music representation and a younger, naive ideal of the female gender.

Nevertheless, over recent years, female portrayal in songs have begun to grow more positive. Dibbens argues that the word “girl” which in the past has been linked to submissiveness and sexualization of women has been reclaimed in recent decades to mean an autonomous and empowered female representation. Dibben argues that popular female artists have begun to shed away from demeaning female representations and reinvented the term to be associated with more positive connotations. The Spice Girls popular song “Girl Power” is an example of this reclamation.

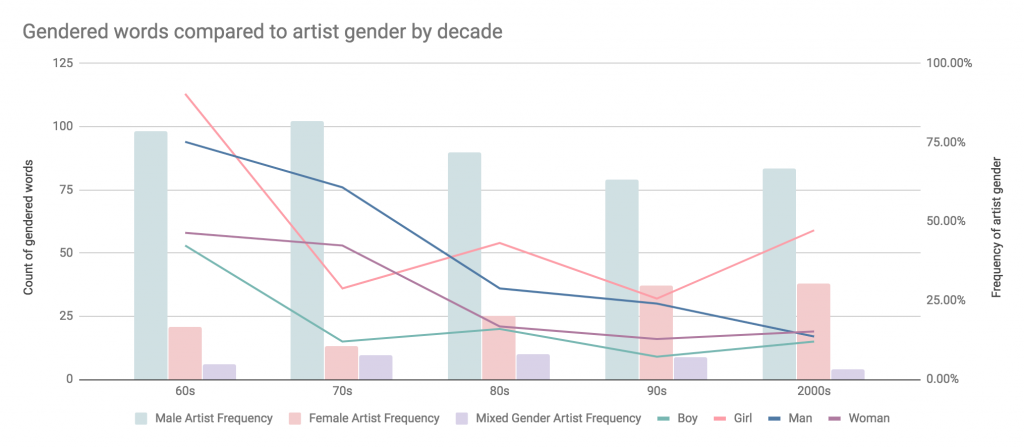

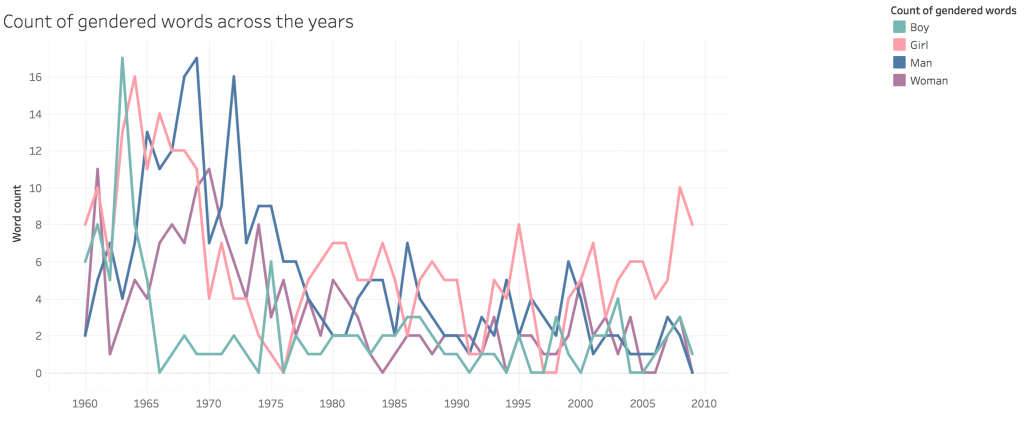

Timeline of frequency of gendered words across the years

This is a line graph of the number of gendered words in the song titles per year from 1960 to 2009. We decided to focus on “girl,” “woman,” “boy” and “man”.

Abramo gives an interesting perspective on gendered words. He argues against the view that the term “woman” will always have a subordinate status to “man.” He says that this claim is an attempt to label the gender “female” as inferior (Abramo 2009). We agree with Abramo’s opinion and have found that gendered words such as boy, girl, man and woman have been used less and less in popular music over time. This can be demonstrated in the above visualization. Perhaps the noted decrease in these gendered words over time shows less emphasis on gender differences.

Significance

In creating this project, we wanted to emphasize the importance of promoting a more representative gender ratio in media and illuminate the prejudice in the music industry. Female artists have long described their struggle to succeed in comparison to men and these numbers show that their stories have objective merit. While additional research beyond this dataset is required, we do believe that diverse representation of women in the music industry has affected the gender conversation in the media we consume today. Of course, despite increased female representation in recent years, the struggle is far from over. More research and efforts from both consumer and industry executives are needed to truly create a representative soundscape.

Our project helps combat this struggle because it offers a unique perspective on the potential for representation to cause societal change. By analyzing the text of the most popular songs, we believe that we can draw insights on gender bias in American society on a much broader scale than typically researched. We believe our results show that representation does shift attitudes on gender. We hope that current female artists and representation will change the dialogue on women and theorize that increased female influence creates a positive feedback loop of change. The upwards trend of non-sexist dialogue in music will continue, encouraging more female artists to join. This will only promote positive dialogue, until the music industry is truly representative. As music adapts to advancements in technology, we can only hope that how we view female artists and talk about gender in songs will evolve as well.

Conclusion

Gender of artists affects the content of gendered words within popular songs. Though men have historically dominated the popular music charts, our data suggests that the last four decades have shown a steady increase in female representation. This growth correlates with an overall decrease in gendered phrases and a recent reclaiming of the word “girl” by female artists.

Though more research is needed, we believe that an increase in female artists has influenced a more inclusive era of music. Gender ratios are beginning to match the 50/50 male to female ratio of American society. Of course, representation is more than just statistics. Instead of men having a majority of the power and space to define women in popular culture, women can now join in and represent themselves.

Overall, our project aimed to analyze how this increase in female artists between the periods of 1960-2010 affected the popularity of certain words. It can be argued that gender distribution within the music industry has helped redefine the way new generations view and hear women, as female equality has been more fought for and expected nowadays than ever before. Our research findings hint at a positive movement towards gender equality within the music industry.